|

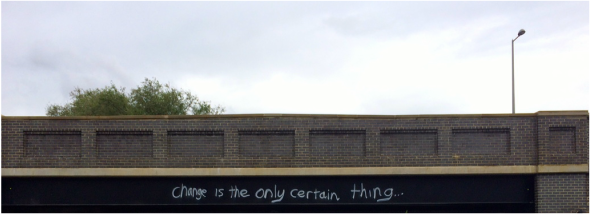

How do we deal with change and the instability it brings?

Does change always feel like a threat? We seem to be in the habit of resisting change, and seizing up or tightening down around something fixed when we feel unstable. We know that humans habituate quickly. If an environmental factor, like the noise of your neighbour’s boiler, happens regularly enough, we stop giving it our full attention and absorb it into our global picture as background noise. This is useful, because without this mechanism, we would be exhausted before we left the house each day, processing every piece of stimulus as if it were important information. Unfortunately, when we overuse habituation, we become desensitised, rigid, and lose our responsiveness to more than just the inconsequential noises of the neighbourhood. We entrain to certain rhythms and patterns and experience them as fixed, and therefore reliable, things. But nothing is in fact, fixed. Everything is in a state of change. At different rates, of course – the tree that your grandfather climbed will look almost exactly the same when your grandchildren climb it, except for a few more branches and a bit of unnoticeable girth. But it’s not static. The pattern of the sun, rising and setting every day, is pretty reliable. But over the course of a year you will see that pattern shift to allow longer days and shorter nights in the summer time. The sun will rise again tomorrow, but not in quite the same way as it did today. Even your body isn’t the body you had seven years ago. Your epidermis has been with you for less than 35 days. Your liver has only been there for six weeks, and even your skeleton is regenerated every 3 months. The problem is that because we have habituated so much, we cease to be attuned to the fluid nature of things. So when the life cycle of an oak tree turns a corner, we are shocked to find a strong wind can knock it down. We have habits of moving through the world in a particular way. Repeated movement in a restricted pattern, like sitting in a chair for most of the day, or typing on a keyboard, will set up a rigidity in the body. When we seek to reclaim the full range of motion that is in our design, we often find resistance in the soft and connective tissue. Even the nervous system can effectively seize up around the action – instead of the acetylcholine that initiates a muscle contraction being used up and effectively replaced with adenosine triphosphate to allow its release, the bodymind can refuse to let go. And then we have rigor, or rigidity. You sit for too long and you feel stiff when you stand up again. And if you have to jump up quickly? Not likely. I know a woman who went live in Seattle, Washington in the early 1960s. This was during the height of the Cold War. The threat of nuclear attack was part of the daily experience, with educational films shown to schoolchildren about how to ‘duck and cover’ in case of nuclear war, and bomb shelters being built by every homeowner who could afford one. Seattle is notorious for it’s weather – low cloud grey skies and soft rain for months on end with no sign of the sun. One day, while she was riding a bus to work, and there was a sudden blinding flash of light in the sky. The bus stopped. Everyone held their breath, wondering if this was the day that history had prepared them for. After a moment, the bus driver spoke into his public announcement system. “Ladies and gentlemen, please don’t be alarmed. There’s nothing to worry about. That was the sun.” What do we do when we have to face change, and the instability it brings? We have to cultivate the ability to sit with discomfort. Listen to it, and relax around it. Tightening down around mere discomfort will only create the pain we fear. We must cultivate flexibility, so that we can access a fuller range of our potential for movement, expression, communication and connection. Because the habits we have now won’t address tomorrow’s needs. And the aspects we imagine to be fixed, around which we anchor our lives, are changing. If we don’t learn to breath into the discomfort of change, we will suffocate. We need to differentiate more effectively between what is actually pain: a signal that some threat to our well-being is present and needs addressing, and discomfort: a sign that change is allowing us a chance to practice our flexibility and enjoy the stretch. We must learn to value the experience of being alive in our bodies, with this gift of perception and interpersonal connection. We must become more of what are: living, moving, becoming creatures. |

About me.I am fascinated by the ways in which we do and don't embody our selves. I do my own kind of research, and coach people to live their truest lives. I practice healing and communication arts, and I write about all these things. I am a nomad, these days living and travelling on my boat in the U.K. Categories

All

Archives

July 2018

phone: +44 (0)7963898806

skype: Genevieve_coach

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed